How to Pick the Right Metrics?

Measuring What Matters and Building Great Products

The Analytika is a dekadal newsletter that is delivered directly to your email. It focuses specifically on the topics of data and business analytical techniques for product managers.

Metrics and Product are kind of two sides of a coin. Nowadays, it’s too hard to imagine a product without someone asking you for feedback. The only way to improve products is by learning from the end-users. Collecting feedback is not only limited to products but also extends to services. For products, setting up a feedback loop is the most important job of a product manager. Having a mechanism to learn from every product release is very critical for success.

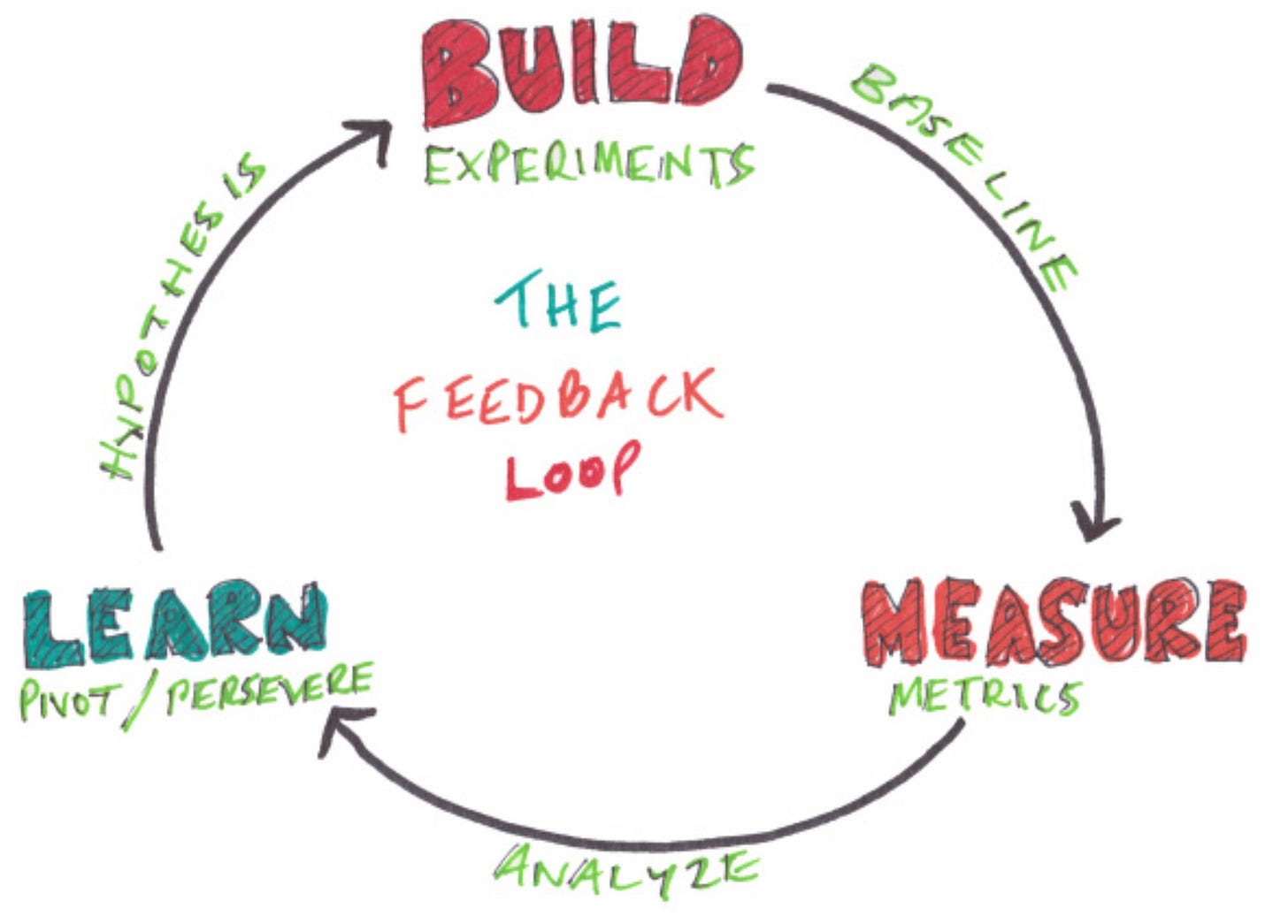

Build, Measure, and Learn, as proposed by Eric Ries in his popular book “Lean Startup” is a great way to establish a feedback loop that enables companies to build products quickly with constant learning from the end-users. It emphasizes two main activities, “maximize learning” and “minimize costs”.

The outcome of Measure and Learn will determine what to Build supporting as a feedback loop. This practice has led to a metrics-driven culture in product discovery and development. Especially, in startups, this practice is highly visible.

To build great products, picking the right metrics and attending them is the key. So, what makes a good metric? Before getting into that, let’s look at the types of metrics and their role in measuring the outcome.

Vanity Metrics

These metrics just make you feel good and they look great on a high level. They do not influence you to take action. They don’t tell you any story. However, they can easily mislead you. Good examples of vanity metrics are:

number of followers

total site traffic

post likes/dislikes

number of subscribers

number of views of the video

number of attendees of a webinar

While they can be very impressive to present, it is worth breaking them down into actionable metrics that are closer to key drivers of the business, such as monthly new followers, site traffic trends, monthly new subscribers, etc.

So, use these metrics cautiously. The best time would be at the early stage of the business just to gain confidence or to document general statistics of the product. Otherwise, stay away from them.

“Vanity metrics are dangerous.”

— Eric Ries, author of The Lean Startup

Actionable Metrics

As the name indicates, these metrics would influence you to take action. They provide valuable insights and drive business growth if appropriate actions are taken. These are the metrics that most product companies track quite often. The data enables product teams to make informed decisions about the direction of a product or organization. Here are some examples of actionable metrics:

Weekly active users

Monthly Recurring Revenue

Churn Rate

Retention Rate

Use these metrics when the business is in the growth stage to track sales, revenue, conversion rate, user engagement, satisfaction, or at the mature stage to track profit, retention length, churn rate, revenue per user, etc.

Reporting Metrics

These metrics are prepared on a day-to-day basis to keep the business management informed on how the business is performing. They are generally picked by internal stakeholders just to get a daily/weekly/monthly/quarterly update on key statistics of the product. Sometimes they are also called “Accounting Metrics.” For example, how many new sign-ups we had today? How many units did we sell this month? How many users renewed last quarter? etc.

Reporting metrics are kind of actionable metrics, but they do not substantially support or influence big decisions as they focus on basic stats. So, do not use these metrics to make any decision that leads to a pivot or a major change in direction. Instead, rely more on actionable metrics.

Exploratory Metrics

If Actionable Metrics influence you to take actions, Exploratory Metrics do one step further. They make you dig deep into the data to find patterns and conduct experiments. These are the metrics you go looking for. Startups quite often use these metrics to generate ideas and scale their business.

One great example of Exploratory Metrics is how the company Circle of Friends became Circle of Moms eventually. When they had 10 million users, the Vanity Metrics did not provide any insight into what type of users mainly use the product. After digging deep into the data, they came to know moms have been mainly using the platform than, in general, “friends.” So, the company immediately pivoted the business, targeting moms and changing its name too.

Other examples of Exploratory Metrics are:

number of sign-ups by age group

number of posts by age group

engagement by gender

Lagging Metrics

With Lagging Metrics, you can only discover the past. They tell you what has happened. They simply report the news about your product. One great example is Churn. It is just a number telling you how many customers dropped off over time. Nothing more. Other examples are:

NPS (Net Promoter Score)

reviews/ratings

revenue (ARR/MRR)

brand recognition

These metrics are easy to measure, but when it comes to improvement. It’s hard. However, they play an important role as part of your KPIs (key performance indicators).

Leading Metrics

If you see your tech support busy in resolving customer complaints, that could indicate that some customers would drop off from service in the future. Unlike Lagging Metrics, Leading Metrics try to predict the future. In this case, we can speculate a number of customer complaints may lead to higher churn down the line if the issue is not addressed. So, they indicate what is likely to happen and an opportunity to change the outcome going forward.

Some examples of Leading Metrics are:

daily/monthly active users to track user engagement

unique visitors

monthly user registrations

Correlated Metrics

By definition, when two metrics are correlated, they behave in a similar way. They have similar trending patterns, and display a seeming relationship, although there isn’t. If you know the trend of one metric, you can easily predict where the other one going. When Statistically, these metrics display a higher correlation coefficient closer to 1 or -1, meaning trending up or down. However, correlated metrics can be completely independent of each other but driven by a third metric that makes them behave in a similar way. This type of correlation is termed as “spurious” by Tyler Vigen in his dedicated book “Spurious Correlations.” This book is all about metrics having a seeming relationship but actually driven by a third metric. It is fun to look at all the charts in this book.

The author of Lean Analytics, Ben Yoskovitz, provides a great example showing a good correlation between metrics ice cream sales and the number of river drownings during the summer month.

When you look at the metrics, you may quickly assume, the drownings are triggered by ice cream sales. But, the reality is, both metrics are driven by warmer temperatures during the summer month. Warm temperatures make more people go to beaches more drownings. At the same time, warm temperatures also make more people buy icecreams. In this case, metrics “variation in temperatures” is the third metric. It is called a “Casual Metric” that we will discuss in the next section.

When you analyze two or more metrics to find a pattern, be sure to check casual factors and understand what could be driving them before making any decisions.

Casual Metrics

As defined previously, these metrics drive other dependent metrics, making them look like they are related. Having a correlation between two metrics is a good thing. Because it helps us predict what will happen in the future, but if you know the cause of the correlation means you can change the behavior. In the above example, the drownings could be reduced by taking other potential measures than stopping ice cream sales. Identifying Causal Metrics is like finding a casualty of a cause. You may have to run experiments on other metrics to understand the actual one-to-one correlation. It’s a rigorous exercise, but it is worth it. Some believe Casual Metrics are the real superpower in analytics and supply the power to hack the future.

Choosing the Right Metric

The metrics types discussed above will just tell you what metric would work out well for you based on your business goals. A good metric is beyond just choosing a type. It must be understandable, comparable, changeable, and it should indicate a rate or ratio. Let’s look at them in detail below.

1. Understandable

A good metric should be very easy to understand when someone looks at it. They should not display any element of complexity. When you prepare a metric, show it to someone outside of your organization. If they can understand the metric easily, it meets the criteria of the good metric. If not, it is complex, and you should address the concerns.

2. Comparable

Just looking at the numbers won’t tell you how better or worse they are if you have nothing to compare it to. A good metric is not only understandable, but it should also be compared with different time periods, users, groups, or competitors. For example, 10% retention in the current month could be alarming if you had 25% retention in the last month. Similarly, it could be delighting if the last month's retention is only 1%. So, a metric with an ability to compare is the right one to pick.

3. Changeable

When you look at the metric, does it make any changes in how you respond? In other words, does it influence you in any way that eventually leads to taking action? If yes, then it is a good metric. Metrics may not reveal this characteristic always. It is not a good idea to stop tracking when you don’t find it “changeable.” You will never know when they become useful. It is better to keep tracking even though they are not changeable.

4. Rate or Ratio

Rates or Ratios are a great way to look at what’s happening or what will be happening. Absolute numbers won’t tell you a story. They are simply just stats. You should avoid them always. It is better to present users as “users per day” or “users per month” instead of reporting total users. Metrics in the format of rate or ratio will also help in the estimation of absolute values and any quick calculations. For example, users per month can help you quickly estimate annual numbers. So, for greater insights, pick the metrics with rate or ratio.

With this, I will wrap up this post.

Takeaway

Just remember! Always start with your business goal in choosing the right metrics. All the metrics discussed here depend on what type of data you collect and how you collect. Analyzing metrics is easy when you have quantitative data over qualitative data. For making any major decisions, always avoid Vanity Metrics and rely on other relevant metrics. Look for casualty when you see a good correlation between two or more metrics. Finding Casual Metrics helps you to build great products. A good metric is easily understandable, comparable, changeable, and a rate or ratio.

And, I will end this post with this beautiful quote by Scott:

“If you don’t collect any metrics, you’re flying blind. If you collect and focus on too many, they may be obstructing your field of view.”

― Scott M. Graffius

References

I couldn’t have written this post without reading the following resources. I highly recommend you to visit the below link to get them for more information about this topic.

Lean Startup by Eric Ries

Lean Analytics by Ben Yoskovitz and Alistair Croll

The Analytika is a dekadal newsletter that is delivered directly to your email. It focuses specifically on the topics of data and business analytical techniques for product managers.

Thanks for reading! I hope you enjoyed this post. Connect with me on Twitter.

-Arjun